What Manuscripts do we Have?

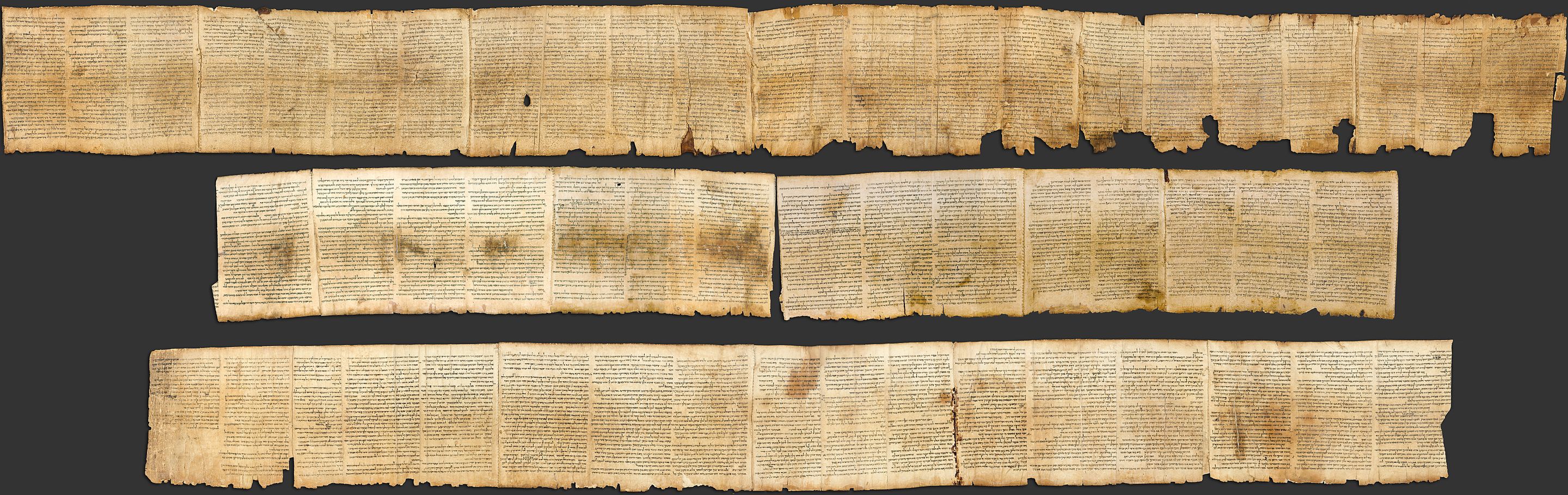

The Great Isaiah Scroll, one of the Dead Sea Scrolls, dated to around 350–100 BCE.

Source: The Israel Museum, Jerusalem

Published on: February 15, 2025

Hebrew Manuscripts and Ancient Translations

Introduction

The textual history of the Old Testament is preserved in various manuscripts, translations, and citations across centuries. These sources provide insight into the transmission, preservation, and variations of biblical texts. The following sections explore key Hebrew manuscripts, ancient translations, and important citations that have contributed to our understanding of the Old Testament.

Hebrew Manuscripts

Hebrew manuscripts form the foundation of the Old Testament. They vary in age, completeness, and textual tradition.

| Manuscript | Date | Key Features |

|---|---|---|

| Dead Sea Scrolls (DSS) | ca. 250 BCE – 70 CE | Includes portions of nearly every Old Testament book. The Great Isaiah Scroll (1QIsaᵃ) is the most complete. |

| Masoretic Text (MT) | ca. 7th–10th centuries CE (based on older traditions from ca. 100 CE) | The standard Hebrew text used in Judaism today. Key manuscripts: Leningrad Codex (1008 CE) (oldest complete manuscript), Aleppo Codex (10th century CE) (partially damaged). |

| Nash Papyrus | ca. 2nd century BCE | Contains the Ten Commandments and the Shema (Deut. 6:4-5). One of the oldest known Hebrew biblical texts before the Dead Sea Scrolls. |

Ancient Translations

As the Hebrew Bible spread beyond Israel, it was translated into various languages. These translations sometimes reflect textual traditions that differ from the Masoretic Text.

| Translation | Date | Language | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Septuagint (LXX) | ca. 3rd–2nd centuries BCE | Greek | The earliest Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible, sometimes reflecting different Hebrew textual traditions than the Masoretic Text. |

| Samaritan Pentateuch | ca. 2nd century BCE – 1st century CE | Hebrew (Samaritan script) | A version of the first five books of Moses (Torah), preserved by the Samaritans. It shows textual differences from the Masoretic Text, sometimes aligning with the Septuagint. |

| Targums | ca. 1st century BCE – 7th century CE | Aramaic | Paraphrases and interpretations of the Hebrew Bible. Key examples: Targum Onkelos (Torah), Targum Jonathan (Prophets). |

| Peshitta | ca. 2nd century CE | Syriac (Aramaic) | A Syriac translation used by Eastern Christian communities. |

| Vulgate | ca. 4th–5th centuries CE | Latin | Latin translation by Jerome, based on Hebrew and Greek texts. Became the official Bible of the Roman Catholic Church. |

Doctrinal Variations Among the Masoretic Text, Septuagint, and Dead Sea Scrolls

| Doctrine | Masoretic Text (MT) | Septuagint (LXX) | Dead Sea Scrolls (DSS) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Messianic Prophecy (Isaiah 7:14) | "Behold, the young woman (almah) shall conceive..." | "Behold, the virgin (parthenos) shall conceive..." | Supports almah (young woman), but some variations include references closer to LXX. |

| Age of the Patriarchs (Genesis 5, 11) | Shorter lifespans (e.g., Methuselah: 969 years) | Longer lifespans (e.g., Methuselah: 187 years older before Lamech's birth) | Confirms both traditions in different manuscripts, showing textual fluidity. |

| Exodus Population (Numbers 1:46) | Over 600,000 Israelite men left Egypt | About 5,500 men left Egypt | Confirms MT’s larger numbers, but some texts suggest alternate figures. |

| Psalm 22:16 (Messianic Prophecy) | "...like a lion are my hands and feet" | "...they have pierced my hands and feet" | Some DSS fragments support LXX reading, strengthening the Christian crucifixion interpretation. |

| Book of Jeremiah | Longer version in MT | Shorter version in LXX (about 15% less text) | Confirms shorter LXX version as older and closer to the DSS texts. |

| Deuteronomy 32:8 (Sons of God vs. Israel) | "Sons of Israel" | "Sons of God" (or "angels of God") | DSS supports LXX’s "Sons of God," suggesting divine council imagery. |

Evaluating the Most Accurate Text Based on Data

The Dead Sea Scrolls (DSS) provide the earliest known Hebrew manuscripts and are crucial for reconstructing the most accurate biblical text. Key insights include:

- The DSS confirm that both MT and LXX originate from earlier Hebrew texts, meaning neither is entirely superior.

- Some DSS readings align with the LXX (e.g., Jeremiah, Psalm 22:16), suggesting that the LXX may preserve older versions in some cases.

- The MT, though standardized, reflects later editorial refinements in Jewish tradition.

From a factual standpoint, a critical Bible edition combining DSS evidence with LXX and MT comparisons would provide the most accurate reconstruction of the biblical text.

Conclusion

The Hebrew Bible's textual history is shaped by manuscripts, translations, and citations that span centuries. The Dead Sea Scrolls have provided valuable insight into the truth, exposing errors made in both the Masoretic Text and the Septuagint while correcting them. These findings contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of the development and preservation of biblical texts.

References

Hebrew Manuscripts

- Tov, Emanuel. Textual Criticism of the Hebrew Bible. Fortress Press, 2012.

- Ulrich, Eugene. The Dead Sea Scrolls and the Origins of the Bible. Eerdmans, 1999.

- Freedman, David Noel. The Leningrad Codex: A Facsimile Edition. Eerdmans, 1998.

Ancient Translations

- Jobes, Karen H., and Moisés Silva. Invitation to the Septuagint. Baker Academic, 2000.

- Brock, Sebastian P. The Bible in the Syriac Tradition. Gorgias Press, 2006.

- Fitzmyer, Joseph A. A Wandering Aramean: Collected Aramaic Essays. Scholars Press, 1979.

- Gentry, Peter J. The Text of the Old Testament: An Introduction to the Biblia Hebraica. Hendrickson Publishers, 2016.

Quotations and Citations

- Metzger, Bruce M. The Early Versions of the New Testament: Their Origin, Transmission, and Limitations. Oxford University Press, 1977.

- Eusebius. Ecclesiastical History. Translated by Kirsopp Lake, Harvard University Press, 1926.

- Origen. Hexapla. Fragments edited by Frederick Field, Oxford University Press, 1875.